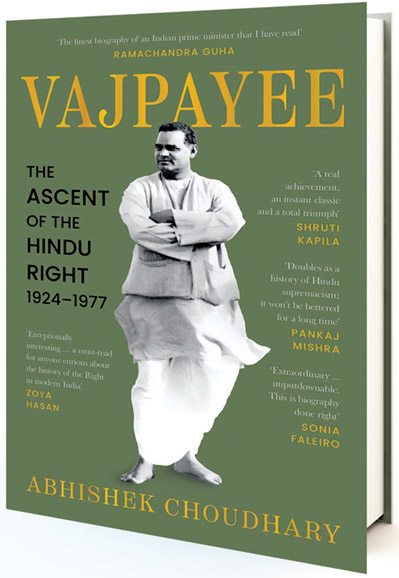

Coming of Age

How the Kashmir issue provided a leg up to Vajpayee’s political career. An extract

Abhishek Choudhary

Mookerji’s first impulse was to agitate on traditional social and economic issues of the day—beginning with food inflation, especially the increase in the prices of rationed wheat. But by the time the Jan Sangh recovered from the shock of defeat, the issue had been hijacked by the communists and socialists, who had fared better at the polls. Low on morale, the party had, its president lamented in mid-May, kept itself ‘aloof as a mere spectator’. The RSS launched a massive signature campaign with the intention to force the government to bring a central legislation to ban the killing of cows. Mookerji sympathized with it from a distance, but did not think it a strong enough plank to start a countrywide agitation. Unable to come up with any new ideas, the party fell back on an old obsession: Kashmir.

Jammu & Kashmir was the only Muslim-majority state of India that was, under Sheikh Abullah’s leadership, determined to remain autonomous. Given their hostile relationship in the past, Abdullah, the new prime minister of J&K, was keen to pay the former ruling class of Dogras back in their own coin. Soon after taking over he had, in July 1950, carried out radical land reforms without paying any compensation, which had hurt many of the Dogra jagirdars. In theory the Jan Sangh supported land reforms, with Mookerji mentioning in his presidential speech of October 1951 that the ‘abolition of zamindari along with other integrated measures will usher in agricultural reforms necessary for the country. But compensation should be paid.’ Since the party drew much of its support form the landed class and some lapsed m

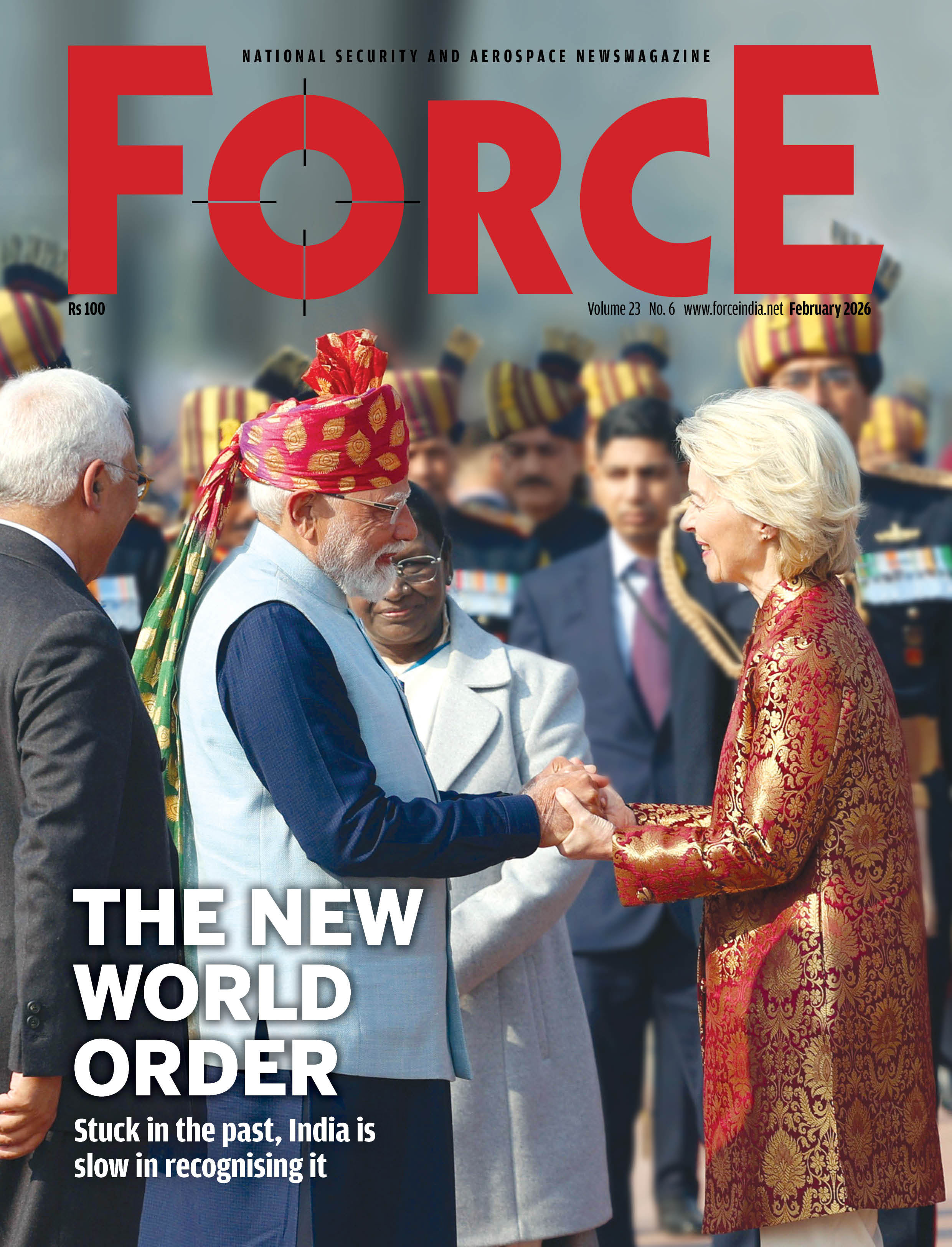

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.

VIDEO

VIDEO