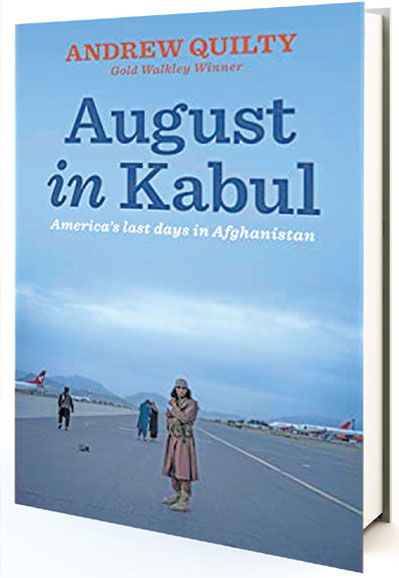

A Tale of Two Armies

Chaos, confusion and desperation in the run-up to US’ exit from Afghanistan. An extract.

Andrew Quilty

(Specialist Nate) Nelson hadn’t expected the Afghanistan he’d learned about through the media and movies over the course of the war, nor that which he’d heard of through the stories of his National Guard sergeants who had already deployed: about IEDs, and a platoon’s experiences in the Korangal Valley, in the country’s north-east, as shown in the documentary film Restrepo. That was because he knew the American involvement in Afghanistan had declined significantly in recent years, and that there hadn’t been a single casualty since February 2020, Nelson’s unit was assigned to diplomatic security, protecting the embassy and the airport using a dozen C-RAMs stationed between the two sites. The ‘diplomatic security designation meant that Nelson and his National Guard colleagues would be staying beyond the 31 August withdrawal date set for foreign ‘combat’ forces.

‘Life really wasn’t bad,’ says Nelson. ‘There were restaurants, all these stores. We had this cafe with a fake garden and fake grass and you could buy a smoothie. I felt like I was on vacation. You could get a massage, you could get a great haircut, the food was actually very good, and we figured we could coast like this until the end of the deployment [February 2022]. Even though the Taliban was taking ground each day, you still felt like the war was a world away.’

In fact, aside from superficial changes, Kabul was closer to the city described by Nelson’s father, who had visited the capital for his work as a cartographer with the British military in the 1960s. Nelson sent his father photos of the bare mountains on the northern side of the airport. ‘Oh,’ his father responded. ‘That all used to be forest. Then the Russians napalmed everything.’ He told Nelson how Westerners would travel to Kabul to ski. ‘It really was like a regular country,’ he said.

Every couple of days, Nelson would check a BBC interactive map contrasting the territ

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.