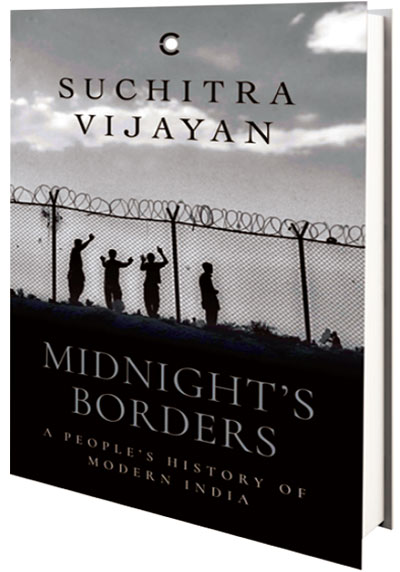

A Line Across People

Why South Asian borders induce distress and dislocation instead of security. An extract

Nagaland remains one of India’s most highly policed states, and the army maintains a permanent presence and surveillance to control all local factions. Votes work on the barter system and remain the most valuable currency. Despite the value of votes, the rule of law has very little currency. Travelling through Nagaland, I found myself in the midst of the two ‘parallel governments’ oppressing their people in perfect coordination and complicity: the National Socialist Council of Nagaland’s (NSCN-IM) Isak-Muivah faction has a Naga Army and there is the Indian Reserve Battalion. The NSCN—a modern Naga separatist group—was formed on 31 January 1980 to oppose the Shillong Accord of 1975, signed as a peace agreement between the previous separatist group, the NNC, and the Indian government. Drug trafficking from Myanmar is reported to be a major source of income for the NSCN-IM, and I heard many stories of extortion and smuggling in regions where the group carries influence. Illegal taxation is rampant. Petty crimes are policed by communities, which take the law into their hands. This is what Indian has to show for itself after seventy years of rule and presence in the region.

The Naga city of Tuensang, difficult to access and situated right on the border with Myanmar, is where the Naga government was first established in 1954. The people of Tuensang continue to find themselves in the crossfire of three opposing and fighting groups—the Indian Army, the Naga underground and the Burmese armed forces. During the height of the insurgency, the Indian Army came in search of Naga underground fighters. The Burmese Army also made incursions into Naga areas to weed out armed groups. The Naga underground groups targeted those they suspected were collaborating with the Indian and Burmese armed forces.

The way to Tuensang was paved with bad roads, and interrupted by blockades and stra

Subscribe To Force

Fuel Fearless Journalism with Your Yearly Subscription

SUBSCRIBE NOW

We don’t tell you how to do your job…

But we put the environment in which you do your job in perspective, so that when you step out you do so with the complete picture.